Gãy xương cột sống do loãng xương

21/04/2019

Loãng xương là một bệnh làm xương yếu và dễ gãy – kết quả là gãy xương (được biết tới là gãy xương do loãng xương). Gãy xương cột sống do loãng xương là một trong những nguyên nhân chính gây đau, tàn tật và đó cũng là một yếu tố dự báo mạnh mẽ cho khả năng gãy xương trong tương lai. Thế nhưng, gãy xương cột sống lại thường không được chẩn đoán, cũng như xác định nguyên nhân để điều trị tận gốc. Điều này đặt bệnh nhân vào nguy hiểm vì có thể phải chịu đựng thêm hàng loạt gãy xương nữa.

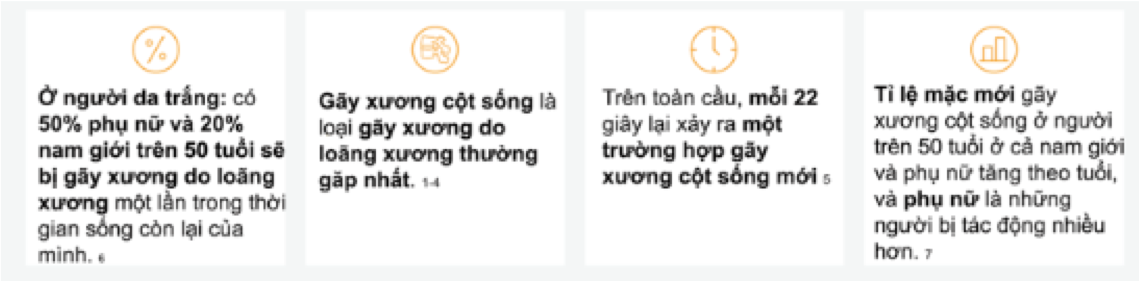

LOẠI GÃY XƯƠNG DO LOÃNG XƯƠNG THƯỜNG GẶP NHẤT

KHÔNG ĐƯỢC CHẨN ĐOÁN VÀ ĐIỀU TRỊ

> Hơn 70% gãy xương cột sống vẫn chưa được chẩn đoán

> Gãy xương cột sống thường bị bỏ qua do các nguyên nhân bao gồm cả bệnh nhân và bác sĩ đều cho rằng đau lưng là do một nguyên nhân khác hoặc bác sĩ không thực hiện các chẩn đoán hình ảnh cho bệnh nhân có nguy cơ loãng xương và đau lưng.

> Thậm chí nếu gãy xương có xuất hiện trên X-quang, khi đọc phim bác sĩ cũng có thể bỏ qua dấu hiệu quan trọng cho chẩn đoán ấy. Tỉ lệ gãy xương cột sống bị bỏ qua trên X-quang được báo cáo là rất cao:

46%: Ở Mỹ La Tinh

45%: Ở Bắc Mỹ

29%: Ở Châu Âu, Nam Phi và Châu Úc

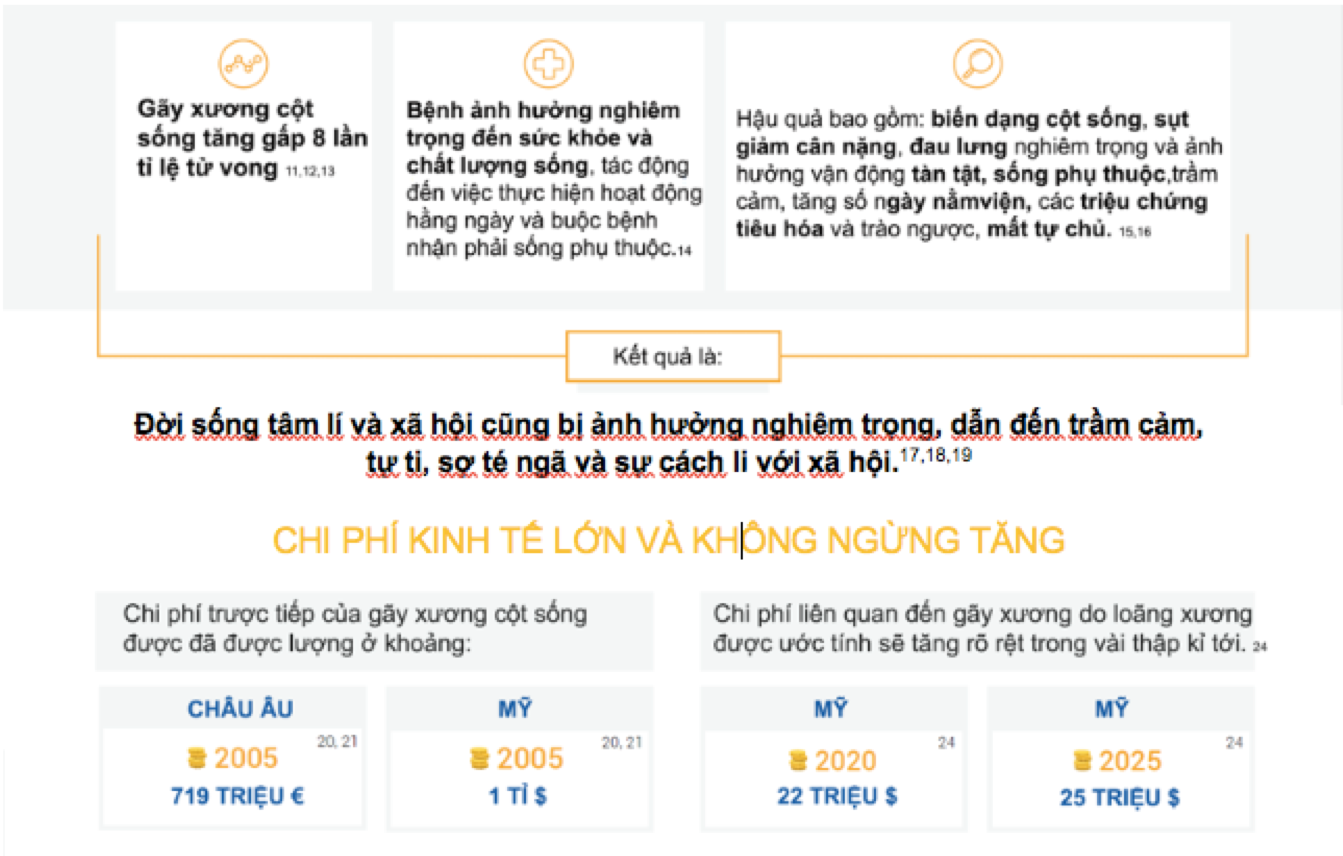

ẢNH HƯỞNG CUỘC SỐNG NGHIÊM TRỌNG

> Một phần ba bệnh nhân gãy xương cột sống đến khám và được điều trị và số ngày nhập viện củ nhân bệnh nhân này nhiều bằng các bệnh thường gặp khác. 22

> Một nghiên cứu ở Vương quốc Anh cho thấy rằng mỗi trường hợp gãy xương cột sống đến khám bác sĩ gia đình nhiều hơn bình thường 14 lần một năm sau gãy xương.23

YẾU TỐ DỰ BÁO MẠNH MẼ CHO KHẢ NĂNG GÃY XƯƠNG TRONG TƯƠNG LAI

CHẨN ĐOÁN SỚM VÀ ĐIỀU TRỊ KỊP THỜI LOÃNG XƯƠNG RẤT QUAN TRỌNG

> Gãy xương cột sống không chỉ làm tăng yếu tố nguy cơ của các gãy xương cột sống mới mà còn làm tăng cả yếu tố của các loại gãy xương khác bao gồm gãy cổ xương đùi.3,8,13,26

20% PHỤ NỮ ĐANG BỊ GÃY XƯƠNG CỘT SỐNG SẼ BỊ MỘT GÃY XƯƠNG KHÁC TRONG VÒNG MÔT NĂM. Nguy cơ tăng lên thuận với số lượng và mực độ nghiêm trọng của các gãy xương cột sống.

> Điều trị loãng xương giảm nguy cơ gãy xương trong vòng 6-12 tháng xuống 50-80%.27

> Điều quan trọng là xác định những bệnh nhân bị gãy cột sống có bị loãng xương không hơn là chỉ chẩn đoán loãng xương và cân nhắc điều trị một cách thích hợp. 28

THAM KHẢO

1. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, et al. Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmö. Osteoporosis Int. 2000;11:669-74.

2. Samelson EL, Hannan MT, Zhang Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors for vertebral fracture in women and men: 25-year follow-upresults from the population-based Framingham study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1207-14.

3. Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L, et al. Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures.Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:821-28.

4. Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, et al. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721-39.

5. Johnell O and Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures.Osteoporos Int 2006; 17:1726.

6. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon-General, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, Rockville (2004)

7. G. Ballane, J. A. Cauley, M. M. Luckey, G. El-Hajj Fuleihan. Worldwide prevalence and incidence of osteoporotic vertebral fracturesOsteoporosis International May 2017, Volume 28, Issue 5, pp 1531–1542.

8. Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA 2001; 285:320.

9. Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallen WM, Melton LJ 3rd.Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population based study in Rochester, Minnesota. J Bone Miner Res. 1992; 7:221-7.

10. Delmas PD, van de Langerijt L, Watts NB, et al. Underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures is a worldwide problem: the IMPACT study. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20:557.

11. Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, et al. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporosis Int. 2000; 11:556-61.

12. Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Vertebral fractures and mortality in older women: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(11):1215-20.

13. Jalava T, Sarna S, Pylkkänen L, Mawer B, Kanis JA, Selby P, et al. Association between vertebral fracture and increased mortality in osteoporotic patients. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(7):1254-60.

14. Hall SE, Criddle RA, Comito TL, Prince RL. A case-control study of quality of life and functional impairment in women with long-standing vertebral osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 1999; 9:508-515.

15. Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D, et al. Quality of life in patients with vertebral fractures: validation of the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO). Working Party for Quality of Life of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 1999; 10:150.

16. Life with Osteoporosis the Untold Story. Camerton: National Osteoporosis Society 2014.

17. Gold DT (2001) The nonskeletal consequences of osteoporotic fractures. Psychologic and social outcomes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2001; 27:255.

18. Robbins J, Hirsch C, Whitmer R, et al. The association of bone mineral density and depression in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:732.

19. Lyles KW. Osteoporosis and depression: shedding more light upon a complex relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:827.

20. Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007 Mar;22(3):465-75.

21. Kanis JA, Johnell O. Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporosis Int 2005; 16:229

22. Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon W, Melton LJ. Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Min-esota: 1985–1989. J Bone Miner Res 1992;7:221–7.

23. Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998; 8:611-17.

24. IOF Compendium of Osteoporosis (Edition 2017). International Osteoporosis Foundation https://www.iofbonehealth.org/ compendium-of-osteoporosis

25. Melton LJ 3rd1, Atkinson EJ, Cooper C, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Vertebral fractures predict subsequent fractures. Osteoporos Int 1999;10(3):214-21.

26. Johnell O, Oden A, Caulin F, Kanis JA. Acute and long-term increase in fracture risk after hospitalization for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 2001; 12:207-214

27. Clinical Guidance for the Effective Identification of Vertebral Fractures. National Osteoporosis Society (UK) November 2017. https://nos.org.uk/media/100017/vertebral-fracture-guidelines.pdf

28. Arboleya L, Diaz-Curiel M, Del Rio L, Blanch J, Diez-Perez A, Guanabens N, et al. Prevalence of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women with lumbar osteopenia using MorphoXpress(R) (OSTEOXPRESS Study). Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22(5-

6):419-26.